If you talk about the beginnings of the microcomputer era from the end of the 1970s on the British Isles, then one name cannot be missing: Acorn. And yet this name means nothing to many people today, especially younger people, even though they surely hold technology in their hands x times every day whose origins go back to this computer manufacturer.

Acorn was often referred to as the “British Apple Inc.” because the company stood for many technical innovations and good product design. The products were also often more technically advanced than the commercially more successful competition from the USA.

But to understand why my Acorn Risc PC600 is a special piece of computer history, we need to know the circumstances of how it came to be. Listing the technical specifications alone doesn’t do the computer justice. So let me take you on an exciting journey of an exciting computer.

The history of Acorn

There are many myths and stories about the famous competition between Sinclair and Acorn, the two most famous British computer manufacturers of the 1980s. Chris Curry, one of the later founders of Acorn, had already worked for Sinclair Radionics for many years and was a close confidant of Sir Clive Sinclair (born in 1940, knighted by Queen Elizabeth II in 1983, died in 2021).

Sinclair founded his first company as early as 1961, with which he produced hi-fi equipment and later also pocket calculators. After Curry’s internal move to Sinclair Instruments (later Science of Cambridge Ltd.), he was involved in the development of the first small and inexpensive microprocessor kit, the MK14, which sold well. Spurred on by its initial success, further computers were to be developed. However, both had different philosophies and expectations regarding the development of microcomputers. Curry therefore left Sinclair to found Acorn with Hermann Hauser and a team of computer science students and microcomputer enthusiasts in Cambridge in 1979. Clive Sinclair did not forgive Curry for this step for a long time and from then on they became fierce competitors.

The BBC Computer Literacy Project

In the early 1980s, these two companies, among others, applied for a tender from the BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation), which was looking for an 8-bit educational computer for its television series “The Computer Programme”. At that time, the growing importance of computers and the importance of teaching computer know-how to society at large was recognised in England. Acorn entered the race with the brand new keyboard computer “Proton”, which they had planned as the successor to the “Atom“, and promptly won the contract. A highlight of this computer was the specially developed open system bus, called “Tube“, with which it was possible to operate a second processor. The computer was then officially marketed as the Acorn BBC Micro.

By the way, I can highly recommend the film “Micro Men” on Youtube, which brings the history of the two companies to life in an exciting way. In any case, this 8-bit computer was to be the final breakthrough for the Acorn company through the BBC deal. From then on, Acorn computers were widely used, especially in schools on the British Isles.

Keep it simple

At some point, Acorn became aware of the first computers with graphical desktop interfaces and mouse operation – such as the Apple Lisa and the Xerox Star – and quickly recognised the potential behind them. In addition, the next generation of computers should already have a 32-bit CPU. However, the aforementioned models from Apple and Xerox were still damn expensive and had a complex computer design. So there was no way that a still quite small computer manufacturer like Acorn would be able to develop a 32-bit system with mouse operation. Unfortunately, none of the CPUs available on the market met the expectations, as they did not offer the required performance leap – especially in real-time processing – compared to 8-bit CPUs. Instead, it would have been necessary to implement many functions with additional chips. This would have made the design of the new computer more complex and thus more expensive.

It was therefore decided to develop their own 32-bit CPU from 1983, which was to follow the basic principle, “Keep it simple” – a lot of performance for as little money as possible. This basic principle goes back to the actual chief developers Steve Furber and Sophie Wilson, who were not satisfied with the existing chip designs of other manufacturers for their own computer. In addition, the slogan “MIPS for the masses” was created, which was also intended to show that they wanted to pack as much performance as possible into a chip at a low price. In addition, the new CPU was to come with a cheap plastic housing and without a fan, as this also saved costs. Thus, a new processor had to be developed from the ground up and consistently trimmed to save power right from the start.

No RISC – no fun!

While most previous CPUs were based on the so-called CISC (Complex Instruction Set Computer) approach, in which – simply put – as many instructions as possible are packed into the CPU, Acorn’s new development is a so-called RISC CPU. Since Acorn did not have the huge development resources available as established chip giants and the development time was also very limited, they finally decided on this simpler chip design.

RISC stands for Reduced Instruction Set Computer. Simply put, it follows the principle of a reduced instruction set, which in turn has a positive effect on processing speed. The reduced instruction set leaves more space for registers, allowing more fast register-to-register operations instead of slower memory-to-register. Although RISC already had a long history of development, as it was used in the first supercomputers of the 1960s, it was not until the Berkley RISC and Stanford MIPS projects in the 1970s/80s that it became popular and led to new processor designs. The best-known representatives here are DEC Alpha, SPARC, HP PA-RISC, RISC-V or Intel i860. Acorn took up this concept for the development of their own 32-bit desktop CPU in order to build it into cheaper microcomputers for the first time. They called it the “Acorn RISC Machine“, abbreviated ARM. In an interview from 2015, Sophie Wilson retrospectively explains the special features of the processor design as follows: Actually, it should be called “Reduced Instruction Complexity Set Computer”, because it does not mean that the CPU processes fewer instructions, quite the opposite, only the complexity of the instructions was reduced. It was recognised that only about 20% of the instructions of conventional processors are used frequently. As an example, she mentions the omission of a devider function that is not used so often and that could easily be replaced by the combination of a few other instructions.

ARM today

But wait a minute! ARM? Aren’t those the processors in modern smartphones? That’s absolutely right! The origins of modern smartphone CPUs actually go back to the development of Acorn. However, the abbreviation ARM later stood for “Advanced RISC Machine” and now the company is simply called “arm” (lower case) and supplies corresponding processor designs that are now licensed by many different manufacturers to use in their own CPUs. They are, so to speak, the further development of the first ARM processors originally brought to life by Acorn. Today, ARM processors are produced in many variants and used in billions of devices, ranging from smartphones to real-time applications in the automotive sector to servers and as the Apple M1/M2 processor in the high-end models of the Macbook Pro.

Incidentally, Apple was one of the first to recognise the potential of ARM CPUs – especially because of their low power consumption – and took a stake in Acorn’s CPU division, now spun off in a joint venture with Acorn, Apple and VLSI Inc. as early as the late 1980s. The ARM processor division was separated from Acorn especially for this deal with Apple, as Apple did not want to cooperate with a direct computer competitor. Apple and Acorn then each took a 43 per cent stake in ARM. Apple first used ARM chips in the PDA Apple Newton, which was only moderately successful. The breakthrough came much later – after the return of Steve Jobs – with the iPod, which had a dual-core ARM running at 90 MHz. By the way: the CPU initially used in the Apple Newton was an ARM610 with 20 MHz and differs from the one in my RiscPC only in the clock frequency.

A little raspberry conquers the world

To bring things full circle: 10 years ago, a Cambridge-based foundation developed a small, inexpensive single-board computer for school classes, which they gave the cute name “Raspberry Pi“. This small educational computer is also powered by an ARM processor, manufactured by the company Broadcom, and runs Linux or RISC OS Open, among other operating systems. In the meantime (as of February 2022), more than 45 million units of different model variants of the little raspberry have already been sold. This makes the Raspberry Pi the best-selling British computer.

Acorn Archimedes

But back to the beginnings: In any case, the first internal tests with the prototype ARMv1 (4 MHz), which was developed under the leadership of Steve Furber and Sophie Wilson, were so successful that it was decided to build the series model ARMv2 (ARM2 and ARM3) into the new Archimedes product series from 1987 and to clock it directly at 8 MHz. Tests showed that these computers were about four times faster than the competitors Sinclair QL, Commodore Amiga and Atari ST with Motorola 68000 processor at practically the same clock frequency with an unbelievable 4 MIPS at that time. In addition, the processor had a much lower power consumption. Sophie Wilson explains in an interview: The Acorn Archimedes were the fastest computers in the microcomputer market at the time. It was only much later, when Intel launched the Pentium I processor, that the competition was able to compete with Acorn – but the Pentium chip had a terribly high power consumption compared to the ARM processor.

For the later, cheaper Archimedes A3010/3020 models, the world’s first SoC (System on a Chip) was developed almost as a sideline by integrating the memory, IO and video controller into the processor, thus achieving further cost savings.

My RiscPC

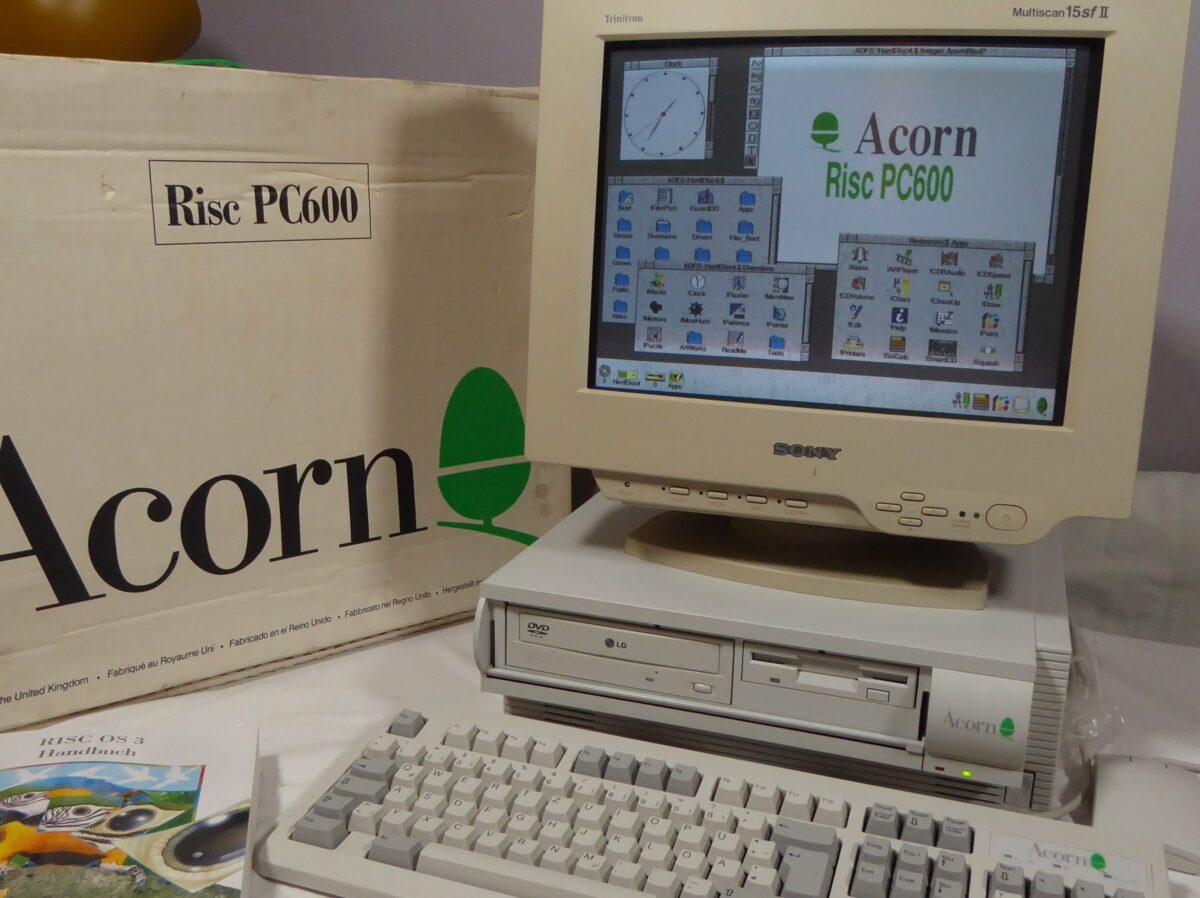

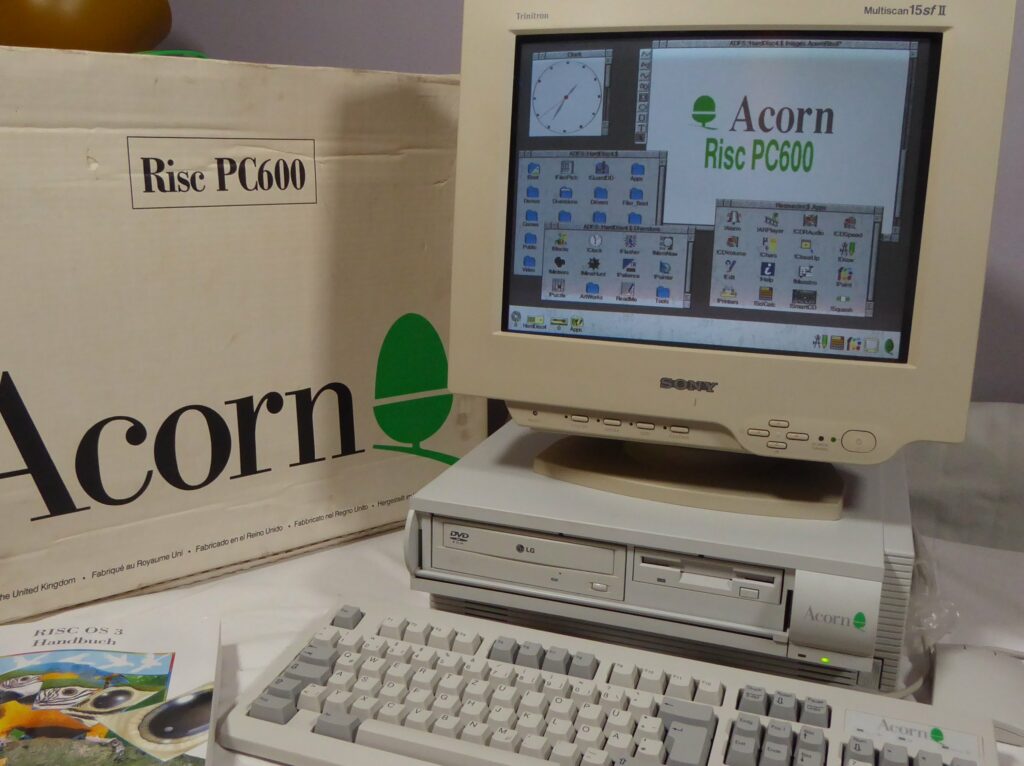

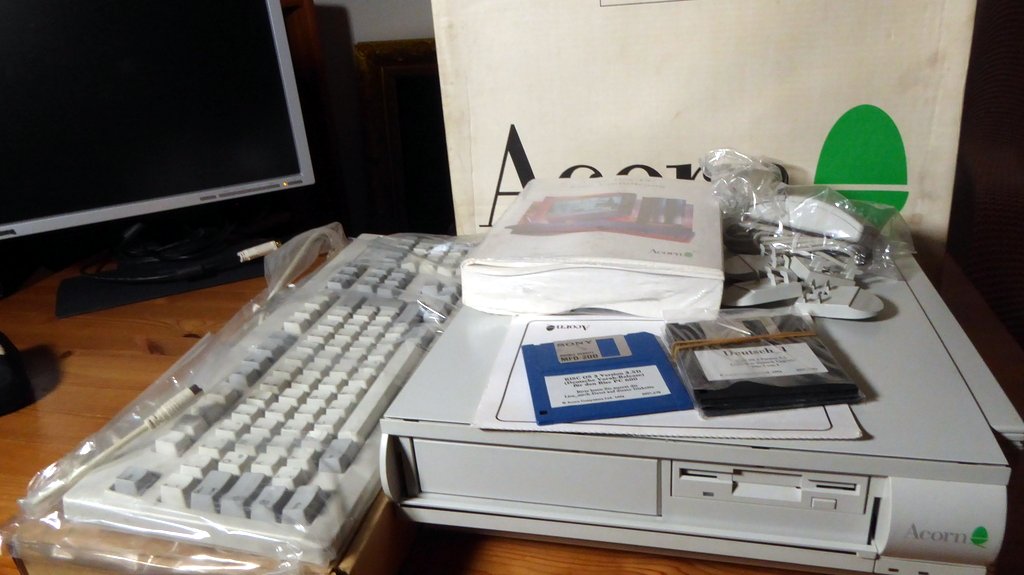

Finally, the further development ARM610 (ARMv3) with 30 MHz clock frequency is the heart of my Acorn Risc PC600, a desktop computer series available on the market from 1994, which was sold in Germany with 4 MB RAM and 210 MB hard disk for 2,999 DM. My computer is a very early model with a low serial number and landed with me in almost new condition with all accessories and original box. The PC 600 is really a chic, compact desktop computer with some highlights that I would like to present to you a little more closely here.

The enclosure

Let’s start with the obvious external highlights: In addition to the 3.5″ floppy drive, the basic version of the enclosure only offers space for a 5.25″ drive. However, the enclosure can be expanded in a very innovative way by adding modular stackable frames (slices). If you put more frames on top, you can add more drives and plug-in cards. Moreover, no tools are needed to open the case. Instead, it is held together with bolts that can be easily opened by hand with a quarter turn. By the way, this very revolutionary case design was created by “Cambridge Product Design”, who have been working with Acorn for a long time and previously designed the cases for the BBC Micro and Electron.

The heart, the CPU

If you take off the top cover, further special features open up. The CPU, for example, is not mounted on the mainboard, as is usual with other PCs, but is inserted upright as a small plug-in card in a processor slot. Next to it is space for a second processor card, into which a 486 SX/DX-compatible CPU extension can be inserted. Thus, both a RISC and an x86 (CISC) system can be operated in parallel. However, several RISC CPUs can also be installed in parallel. It can also be exchanged for a higher-performance model. This modular CPU design makes the Acorn RiscPC extremely flexible, something that is only known from much more expensive workstations. Incidentally, this multi-processor design was made possible by a specially developed interface, called “Tube”, which had already been introduced in the BBC Micro. A few years later (1997), the StrongARM CPU, the flagship for RiscPCs, was released in cooperation with DEC. It was also available as an upgrade for the PC 600 and, with its 230 MIPS, was a real 486 and Pentium killer.

In any case, I’m interested in equipping the computer with an Intel 486 PC card in the near future, e.g. to run Windows 95 in a window under RISC OS – just to see that it works. I still have a 486 CPU lying around. And if you put it side by side with the ARM processor in a size comparison, it becomes clear just from the outside what a revolutionary processor design ARM is. The ARM610 CPU 30 MHz (26 MIPS) with 4 kB cache and integrated MMU looks rather inconspicuous. The small dimensions of the die were also possible because the processor hardly generates any heat. In contrast, the 486 CPU gets terribly hot after only a few seconds and therefore requires additional active cooling. The ARM, on the other hand, does not need a processor fan at all. Acorn thus impressively proved to the world what efficient processor design is!

Without NIC

A network connection is missing from my basic equipment, but it can be retrofitted as a so-called piggyback plug-in card on the mainboard. There are different versions for 10-Base2 (BNC) and/or 10-BaseT (RJ45). Furthermore, there is a so-called riser card on the mainboard with two slots for further extensions – called podules at Acorn – e.g. for a SCSI card.

Memory

In addition to the two EDO SIMM slots for up to 256 MB RAM, there is another slot for a VRAM module. This allows the VGA graphics memory to be flexibly expanded by 1 or 2 MB in order to obtain a higher graphics resolution and colour depth, which is highly recommended especially when connecting modern VGA screens. Furthermore, a 3.5″ IDE hard disk from Conner with 210 MB capacity is installed in the housing.

Graphical Operating System

The scope of delivery includes the operating system RISC OS in version 3.5. It is very unusual that it consists of two ROM modules that are socketed on the mainboard. Actually, since the IBM PC at the latest, it has been customary to load the operating system completely from the hard disk or floppy disk. The advantage of the operating system in ROM is a faster boot process, but it is not so easy to upgrade to a new version, because the ROM modules have to be replaced. Unfortunately, the original version 3.5 installed on my computer also contains some bugs and lacks the CD-ROM driver, among other things, which is why Acorn quickly released a version 3.6 at that time. The subsequent version 3.7 was the last operating system version released by Acorn before the company was restructured.

Since my RiscPC is only equipped with a hard disk and a 3.5″ floppy, it would of course be nice to retrofit a CD-ROM drive in the free 5.25″ slot. In the meantime I have found out that the CD-ROM driver can easily be installed under version 3.5 of RISC OS, as explained on the following page: https://stardot.org.uk/forums/viewtopic.php?t=12951.

An advantage is that RISC OS also supports MS-DOS formatted floppy disks by default. This makes the exchange of files with the DOS/Windows world very easy. RISC OS, on the other hand, formats 3.5″ HD floppy disks with its own file system ADFS (Advanced Disc Filing System) and a capacity of 1.6 MB and is therefore not compatible with the IBM PC.

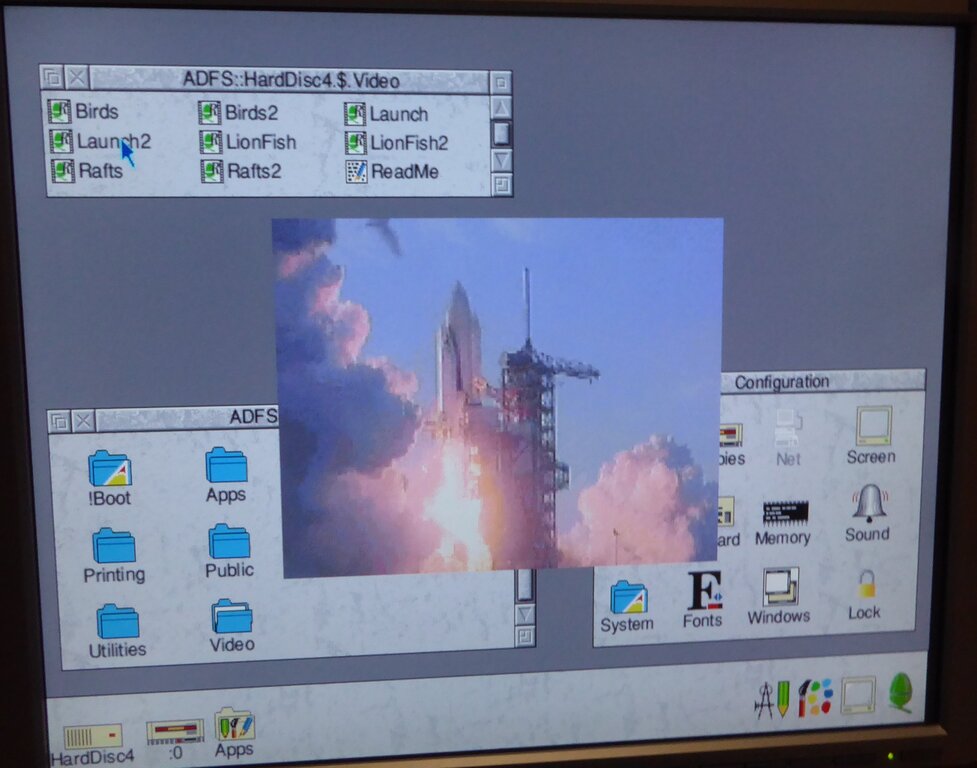

The operating system RISC OS was developed especially for computers with the ARM chip. However, the first Archimedes PCs in 1987 were still the predecessor called “Arthur”, which was even partly written in BBC BASIC and did not yet support multitasking. Its successor, the RISC OS, was written entirely in assembler. The operating system was consistently oriented towards operation with the graphical user interface (WIMP) and operation with the mouse. A special feature here is that a 3-button mouse is required because the middle button provides the context menu. The operating system is still being further developed today and is now even available for the Raspberry Pi 400 as RISC OS Open.

RISC OS is still pretty new territory for me. But it is definitely exciting to delve deeper here, because it is considered a very powerful operating system. It also includes the powerful BBC BASIC interpreter and some tools for graphics editing and word processing.

Conclusion

As is often the case in life and in business, the more innovative and better product does not always prevail. Acorn Computer had to learn this painfully. In the end, the IBM/Intel/Microsoft superiority was too great for a small company from Cambridge to be able to stand up to it in the long run. Nevertheless, they proved that they could bring great products to the market. Even if Acorn computers no longer exist, at least the ARM processor has survived and started a unique triumphal procession. The revolutionary design with the restriction to the essentials and the associated significantly lower power consumption made many device designs possible that we take for granted today and can no longer imagine life without.

That’s why my Acorn Risc PC600 also gets a special place in my collection.

Anyway, I’ll be sure to report on the RiscPC and RISC OS as soon as I’ve delved deeper into the marterie. First up, for example, is the obligatory replacement of the setup battery. Then I’d like to upgrade to RISC OS 3.7 and give the computer more RAM and VRAM, as well as a network card. And finally, I’m interested in a second processor card for my existing 486DX CPU to run Windows 95.

In the meantime, I recommend another great article about Acorn and the ARM processor by blogger Andreas on his site digitalesleben.blog. There you can learn even more about the history of this unique company: https://digitalesleben.blog/2022/06/21/acorn-arm-und-raspberry-pi-die-zukunft-kommt-aus-cambridge/#comment-1075